The UK is getting its own emergency alert system to warn people of any immediate public safety risks.

It will see notifications sent to tens of millions of phones across the country whenever there is a threat to life, from extreme fires to severe flooding.

Only the emergency services, government departments and other public bodies will be able to send the alerts.

Ahead of the first nationwide test on Sunday 23 April, here are some examples of how existing mobile emergency alert systems work in other countries.

US

America uses a system of “wireless emergency alerts”, which – like the UK’s – look like text messages but with a bespoke sound and vibration pattern to get your attention.

Alerts are sent over cellular masts and are little longer than a tweet, with each capped at just 360 characters, and include details like the type of emergency and what action you should take.

They will also have a timestamp and tell you which agency has sent the warning.

National, state, and local public safety officials can all send them – so can the National Weather Service and the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children.

You might even get one from the president, should the situation demand it.

But it doesn’t always go to plan. In 2018, Hawaiian authorities accidentally warned people of an incoming ballistic missile strike.

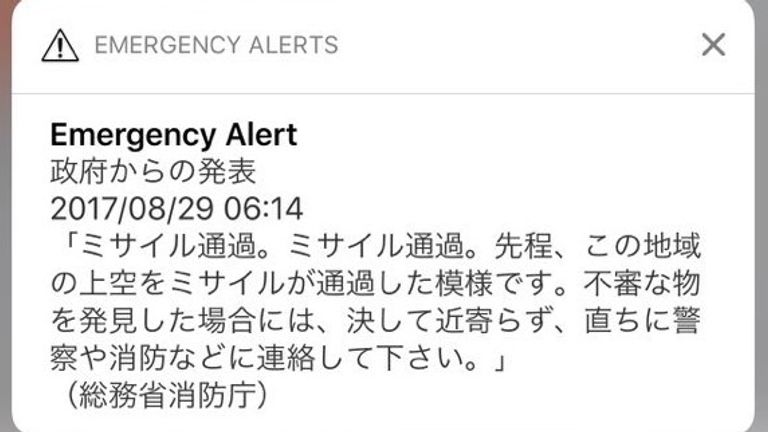

Japan

Japan‘s mobile phone alerts are part of a wider scheme called J-ALERT, which also broadcasts warnings on TV, outdoor speakers, radio, and by email.

The alerts are delivered by push notification to any handset using a SIM card from a Japanese network, but there are also specific apps which support J-ALERT – handy if you’re travelling.

Among them are NERV, a disaster prevention app, and the NHK World TV news app.

J-ALERT is used for natural disasters such as earthquakes – and sometimes in the event of a test ballistic missile launch from North Korea (real ones, in this instance).

Australia

Emergency alerts in Australia are literal phone calls and text messages.

The country’s warning system, which is used by emergency services during incidents such as bushfires and when someone goes missing, sends voice messages to landlines and texts to mobiles.

It means there is a number that people are encouraged to add to their contacts and not block: +61 444 444 444.

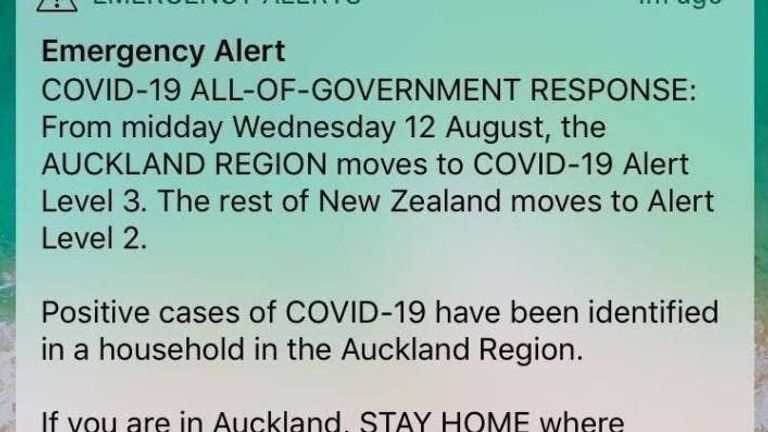

New Zealand

The system in New Zealand works more similarly to the US than it does in Australia, with alerts broadcast to any capable phones from signal masts.

But it does mean that older handsets may be out of luck, and the government keeps a list on its website of all supported models. People are also encouraged to ensure their device’s software is fully up-to-date.

New Zealand’s emergency alerts got a good workout during the COVID-19 pandemic, but are otherwise only used when there’s a “serious threat to life, health, or property”.

Like the UK’s upcoming pilot, test alerts are also occasionally sent out.

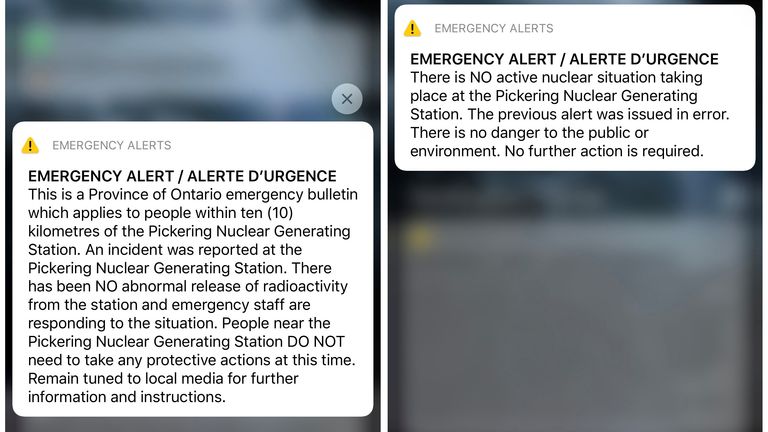

Canada

All wireless service providers in Canada are required to send emergency alerts to devices on their networks.

They have a unique vibration to distinguish them from other notifications, but use the same tone that people will recognise from alerts broadcast on radio and TV.

Emergency services send them to warn of “imminent or possible dangers”, including floods, fires, and tornados.

They can also be used for other incidents – again in the case of missing children, for example. And like the UK’s, any alerts can be sent out at an extremely local level.

Two test alerts are sent each year, usually in May and November.

In 2020, an emergency alert warning millions of people of an “incident” at a nuclear power plant near Toronto was pushed out in error.

Netherlands

Appearing to take a cue from the Japanese with its name, NL-Alert is the Dutch alert system.

It is used in life-threatening situations like a major fire, terror attack, or public health emergency.

By contrast, it’s understood that the UK system has not been designed with terror attacks in mind.

Once again, the system uses cellular masts to avoid overloading the phone network, so does not need anyone’s number to push out the alerts.

Like Canada, the government sends out two tests a year – on the first Monday of June and December at noon.

An extra feature of NL-Alert is that it’s increasingly being rolled out to digital advertising displays and signs, with warnings coinciding with those sent to mobiles. They show up at places like bus stops and train stations.

France

Another familiar name, FR-Alert has been operating across France since 2022.

It sends mobile phone notifications to everyone in the area, warning of a major incident, including extreme weather, health emergencies like a pandemic, serious road and rail accidents, and terrorist attacks.

The alerts come with their own sound and vibration, and include details of the nature of the risk, the location, the authority behind the warning, and any advice – like stay at home or leave the area.

Like with most other countries’ systems, they are broadcast by masts rather than as standard text messages – but people with older devices limited to 2G and 3G will get an SMS instead.

That’s how the UK government has previously had to send out national alerts, such as lockdown announcements during the pandemic.