From climate scientists, the September temperature data has prompted a string of superlatives: “gobsmackingly bananas”, “unprecedented”, “staggering,” “unnerving”.

A look at the data they’re reacting to – and it helps explain why.

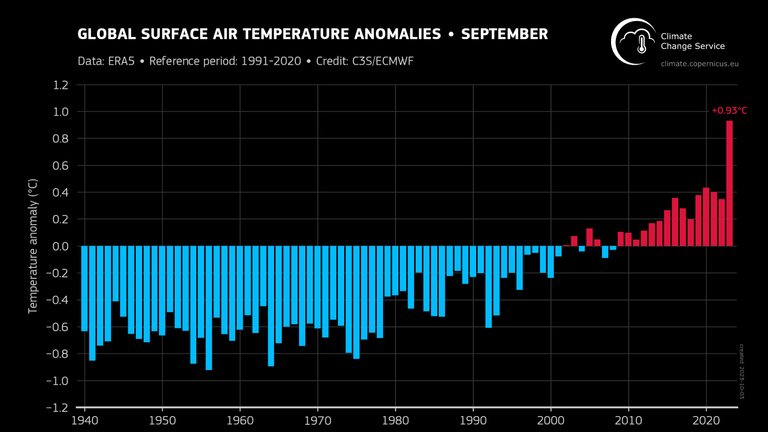

September 2023 hasn’t just broken the record for the warmest September on record, it obliterated it.

It was half a degree warmer than the previous warmest September (2020).

If that doesn’t sound like much, remember this is a global average temperature, compiled from satellite data and monitoring stations covering the entire globe.

It was nearly a degree warmer than the recent average for September.

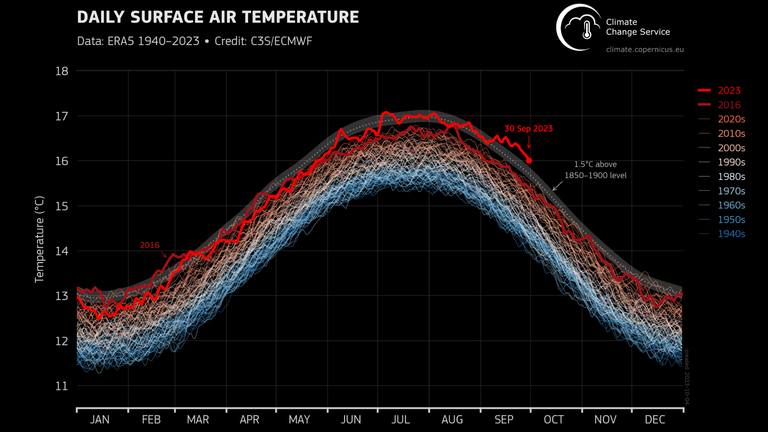

And compared to pre-industrial times – before greenhouse gasses began warming the atmosphere – it’s 1.75 degrees warmer.

Another reason for experts’ open mouths is that the extremes have kept coming. June, July and August were also unprecedentedly warm.

The researchers at the EU’s Copernicus climate monitoring service that produced this latest analysis are now predicting 2023 will be the warmest year since records began, taking us into a global temperature regime we’ve not seen for around 120,000 years.

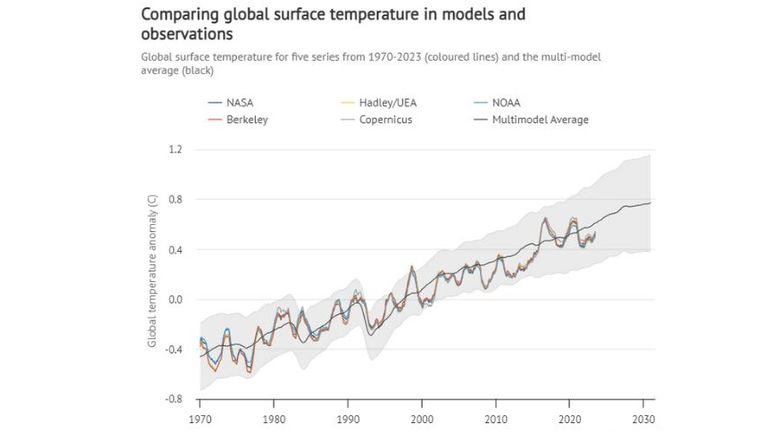

The huge departure from previous averages – in the context of an already-warming world – have prompted some to suggest climate change is accelerating.

But, for now, at least, there’s no clear evidence that’s happening.

The above chart compares the leading sources of global temperature data (coloured lines) with the average of all the climate change models used to forecast the amount of global warming we expect as greenhouse gasses increase (the shaded area is the model uncertainty).

Despite the recent extremes, average global temperatures are climbing in line with what climate scientists have been predicting for decades.

But what is baffling researchers is why the extremes we’re seeing in certain parts of the world are just so much higher than many had expected.

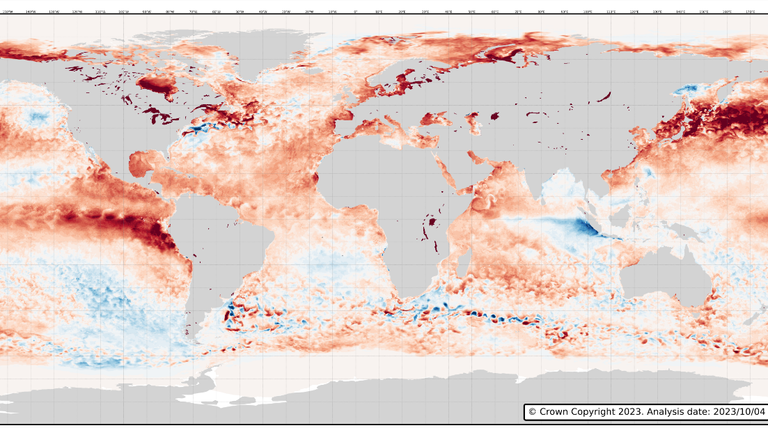

El Nino, the cyclical weather phenomenon in the Pacific is certainly giving a major boost to current global temperatures.

The strengthening El Nino is injecting a pulse of heat into the global climate system that’s helping push 2023 to be warmer and helping drive weather extremes too.

The abnormally high ocean temperatures off the west coast of South America seen in this satellite data is one of its hallmarks.

But they suspect there’s more going on than that.

The Atlantic Ocean has also been significantly warmer than normal. It is unconnected to the pacific El Nino system.

Yet warmth there is implicated in turbocharging this summer’s European heatwaves, and increasing rainfall extremes like those seen in New York last week.

No one is precisely sure why, but various climate feedbacks, like melting ice sheets impacting ocean currents and allowing the ocean to absorb more heat is a possibility.

The record-breaking loss of Antarctic Sea ice this year could be both a symptom and a cause of the current temperature anomaly.

Other factors under investigation are the 11-year cycle of solar activity, a fall in pollution from the world’s shipping that could be allowing more ocean heating by the sun, even a major volcanic eruption in Tonga last year.

While the reasons for these worryingly warm few months are still unclear, what’s in little doubt is the impact they’re having.

The severity of heatwave, fire, rainfall and storm events around the world are being exacerbated by the heat in the atmosphere.

Read more:

Switzerland has lost 10% of its glaciers in just two years – study

Extreme global warming ‘could eventually wipe out humans’

So, while the rate of warming we’ve seen in the last few months is likely to slow as El Nino abates, the long-term trend will continue as long as greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise.

This September was 1.75 degrees warmer than the pre-industrial average. August around 1.5 degrees.

A foretaste of what things will be like when the world reaches a global, year-round average of 1.5 degrees – the safety limit the world has agreed to try and avoid.

“This is a warning,” said Ed Hawkins, professor of climate science at the University of Reading. In a 1.5 degree world, he said, “this type of year will essentially become normal”.